|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home > Treks > Outside Australasia > Mount Kilimanjaro > 6 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Introduction to today's journeyEvery mountain top is within reach if you just keep climbing. - Barry Finlay Today's trek takes me from the basecamp at Kibo leaving at midnight to climb the steep crater up to its rim at Gilman Point and follow the top of the crater clockwise until reaching the summit of Kilimanjaro. From there we return down the mountain initially to Kibo for a couple of hours rest before continuing down the Marangu route back to Horombo. Today's JourneyDistance trekked today: 22 kilometres. Total distance trekked to date: 56 kilometres. I WAS awoken by noisy activity in the bunk room. Feeling quite sick from the room being filled with smoke choking out the already rarefied frozen air, I stirred and came to my senses. The small Japanese group staying in the bunkroom were already up and starting to pack for their ascent to the summit. One of the guys in that group still had his bad hacking cough that he had yesterday. It sounded quite serious in any circumstances, but especially for the conditions he was about to put himself through. He was obviously determined though with the quiet tenacity instilled in the Japanese culture.

I looked at my clock. It was only ten thirty. The others in my group were starting to wake up as well. The mood in the bunkroom was very sombre. It wasn’t exactly good morning. I got up and put on my anorak over my clothes which I had worn in my sleeping bag to stop me from freezing solid. Our porters arrived at eleven o’clock and served us with a small breakfast. It really was just a snack of butterscotch biscuits and tea. I only managed one biscuit and a drink of tea with the obligatory four sugars being over 4000 metres above sea level. I recalled our briefing the other day when Desmond had quoted an early explorer saying that when leaving Kibo at midnight, they would get up, eat breakfast, vomit it all, and then head off up the mountain. Now I could understand that strange story. My appetite was non-existent. The small breakfast would ensure we wouldn’t get too sick though. I really didn’t have much appetite at all. I was nervous about the climb, knowing this was like the final ascent of Kinabalu last year, only a lot worse being so much higher up venturing into very dangerous altitudes and it being so much colder up here. The temperature in the room must be about minus seven degrees Celsius. Goodness knows how cold it was outside. We sat at the table very forlorn with very little energy eating our little snacks. Once breakfast was over we packed up in the darkness with only the light of our head torches. I put my anorak on, and had the small water bottle filled with water to place under my polar fleece top. I packed the camera and other things for the climb. I then double checked my nausea pills and the spare gingko biloba tablets in my pocket. I also checked the chocolate bars in the other pocket even though I had absolutely no appetite. Just feeling the wrapper in my pocket made me feel sick. Then my nose suddenly started bleeding. Fortunately I had my toilet paper handy and put some up my nose. It was one of those anaemic nose bleeds that was never going to stop. This was the worst possible time to develop one, so I made sure the toilet roll was packed up at the top of the bag in case the bleeding continued during the climb. The main camera had to go in the daypack as this was going to be quite a difficult climb up the scree slope and I didn’t want it to get in the way. The small camera in my pocket will be used for any photos between here and Gilman’s Point.

I lay down for a few minutes trying to get the nose bleed to stop. Fortunately it did start to clot but it was obviously not going to stop anytime soon. Was this going to stop me from reaching the summit? I was now feeling quite sick desperately wanting to crawl back into my sleeping bag and curl up into a ball and dream of being in the tropics. Then I remembered I was in the tropics, just a couple of degrees off the equator. We had almost completed packing, and there was a few moments silence before one of the Japanese guys suddenly let out a massive ripper of a fart. Instantly the sombre atmosphere lifted as everyone burst into laughter, including the Japanese guy, the obvious culprit. Truly the most sad or tragic situation can be blown away by an assertive male salute for nothing maketh merrier than the breaking of wind. Though insignificant and perhaps quickly forgotten, I think this moment breaking away from the nervous anticipation and blowing off the altitude sickness was a welcome relief. That would have lifted our spirits just a tiny bit that may very well have assisted some of us getting over the edge to make the difference between reaching the summit or not. Biologically I think the Japanese guy's digestive system was simply trying to reach equilibrium with the much reduced air pressure up here at Kibo. Then again it could just be a reaction to something he had eaten at dinner. Who knows? I hoped this didn’t indicate the start of any of us getting any stomach ailments. Our resident doctor had mentioned just yesterday that farting indicates a healthy body. Clearly this guy was healthy this morning - healthier than the coughing guy in his group who was still going to attempt the summit. What was most important though is we experienced a brief moment of happiness at the start of what will be a very challenging night for all of us. The Japanese guys hurried out of the hut to start their summit attempt. Rugged up and ready to leave, I quickly pulled out my tripod and took my camera outside. There was still about ten minutes to go before we were leaving, so I had a bit of time to sneak in some photography. It was deathly cold outside there, perhaps minus twelve degrees. I set up the camera on the tripod and took a few photos of Kibo Peak directly behind the hut to the west and of Mawenzi Peak now to the east. Both peaks were free of cloud thankfully.

The waxing gibbous moon was shining very brightly, yet the stars were incredibly bright. I imagined what it would be like on a moonless night, seeing the stars at an incredible brightness up here above half the thickness of the atmosphere. The shots I took were all long twenty to thirty second exposures. It was very difficult taking pictures wearing both mittens and climbing gloves, so I had to take the gloves off to give my fingers enough dexterity to make all the camera adjustments and especially to press the button to take the pictures. I took several pictures looking both ways, but with little oxygen in the air and the conditions being so cold, I would have no idea how these shots would come out until I return home in several weeks’ time and publish them. Fingers crossed. The cloud was clearing from the desert in front of Mawenzi Peak revealing Jupiter shining very brightly to its left. There were a few lights from people inside tents. Looking the other way Kibo Peak was a large block of volcanic rock with a few ghostly slithers of glacial ice flanking the left hand side. There were a few pinpoints of light of people who had already commenced their summit attempts. Starting to feel chilled, I quickly packed up and returned inside the hut to where the others were waiting. I put the camera into the day pack and rested with the others. Finally our guides returned ready to take us up the mountain through the deathly cold at these dangerous high altitudes. There is nothing more insane than trekking up a mountain in the small hours of the morning in subzero temperatures. We left Kibo hut just before midnight, entered the frigid cold and commenced our ascent along the steep trail. Ice condensed from the air had frozen the particles of dirt together accentuating the crunching sound of the sand and gravel beneath our boots. Perhaps the still ice air had also improved hearing transmission in this otherwise deathly silent alpine desert too harsh for any life to exist. We followed the stream of lights of people silently climbed the mountain – well silently apart from the crunching of the icy sand and stones. The air was surprisingly still. I would have expected strong winds up here at these altitudes far higher than I had ever been before. The still air at least was one thing we didn’t have to contend with. The track began to steepen, and with it my will to go on started to wane. At other times during the trek we had been talking as we had walked. Now we were all silent. I was second in line at the moment with Jaseri about two metres in front of me. I watched his boots taking one slow step after another. I kept pace with him, and imagined everyone else was doing the same behind me. Or perhaps they were all fine and I was the only one suffering at the moment.

About an hour and a half after leaving Kibo we briefly stopped at a large rock under which were the first small patches of snow on the ground. This was the first time I had seen snow close up within touching distance since last climbing Mount Taranaki six years ago. It was very painful getting up, and Vicky quickly took the spot behind Jaseri. She really liked that second spot and seemed very uncomfortable in any other position in the group. Maybe it was a self-confidence thing so prevalent in Australian society. Dawn was now directly behind me. We were just ten minutes from the first stop when I started to feel sick to the stomach – and very sick at that. I thought I was going to vomit. Some people can vomit and it hardly seems to affect them at all. Other people vomit and they think they are going to die. Unfortunately I am the second type. Last time I vomited was about three years ago when I got food poisoning thanks to buying some junk food from a fast food outlet. I had only vomited twice that evening, but I had felt so ill that I had seriously rethought my life. It was that bad. Otherwise I had only ever vomited after eating chicken flavoured potato chips (which I am apparently allergic to), or in one case when I was a kid eating without washing my hands after touching some deadly hemlock. I couldn’t throw up tonight. As far as I was concerned vomiting would cost me the summit, and I wasn’t willing to let that go at any cost. Well almost not for any cost. I recalled the story of the Japanese woman who had been so determined to get herself to the summit that she had paid the guides a large sum of money to get her up there. On the way up she had actually passed out. Her well paid guides carried her to the top and photographed her before carrying her down where fortunately she did regain consciousness and lived to tell the story. I’m sure though they wouldn’t be allowed to do that these days – Jaseri certainly wouldn’t allow it. If I were to pass out I’m sure they would carry me straight down the mountain no matter how close to the summit I got. Right now that seemed like a good idea. Right now though, I was feeling seriously sick to the stomach. I had climbed to some four thousand nine hundred metres above sea level completely drug free, having only taken my gingko biloba and tried some of Dawn’s magnesium powder. At the time I had actually forgotten about the Imodium tablet I had taken yesterday. Everyone else was on Diamox and had suffered some form of side effects. For a while I thought I was going to complete the entire trip drug free, but now I had to make the decision whether to take a nausea pill and give myself a good chance of staying healthy to the summit, or not taking it and spewing everywhere and potentially losing the summit. Losing the summit was not an option now, so I reached into my pocket, found the bottle of nausea tablets and took one. Now I was officially a druggy, but by this stage I really didn’t care. Within four minutes my nausea had completely subsided and I was feeling much better. No more sickness! Now nothing was going to stop me – or so I thought. The climb up the frozen rubble became steeper and slower as the temperature continued to plummet. Finally at 1:45 AM we reached a small cave where Jaseri told us to rest again.

There was a small faded sign beside us saying that we were at exactly five thousand metres – a place called Williams Point. The sign was old and unreadable, but I still posed next to it. I was now 662 metres higher than I had ever been before this trip. They say that altitudes above five thousand metres are extremely dangerous. Well I certainly didn’t feel safe up here clinging to the side of the mountain in minus fifteen degrees in the dead of night. Fortunately the air was still calm. I pulled the water bottle out from inside my polar fleece top. The water was very cold, but thankfully still liquid. We rested for a few more minutes before I could feel the cold creeping in though all my layers. Fortunately Jaseri told us it was time to continue our climb up the side of the mountain. The slope got steeper and steeper, and suddenly we were crossing from side to side along a loose switchback track across scree. About half way across each crossing of the scree slope the track became almost non-existent as we passed the steep downhill route down the slope. At those points it became rather precarious. I didn’t even think about the downhill. After all I hate downhill with a passion, and had to fully focus all my efforts on reaching the summit at this stage, and that was still a good five hours away. I looked up ahead of me. There were quite a few lights ahead of me all rising very steeply. I felt dizzy and disoriented, so I looked down at the stream of lights below me, and then back up at the boots of Vicky. She was very comfortable in second place behind our leader. It seemed to be her nervous way of coping up here. She didn’t like following me obviously, or anyone else for that matter. Dawn was immediately behind me. Later she would tell me that she had kept her sanity by spending the entire way up the mountain watching and following my boots. She had focused on them so much that she had occasionally banged her head against the back of my daypack. With two cameras in the pack, that couldn’t have done her head much good. I have no recollection though of that happening. I was settling into the routine of walking up the crossing over the slope although the middle of the trail was worn from what was obviously the downhill route. Then Ashley suddenly burst into tears and sobbed that she was feeling very sick and couldn’t go on any further. All she wanted to do was to head back. One of the assistant guides Azaan agreed to stay with her and head down with her. I had remembered what Desmond had said during the briefing, that some people only make it up with the encouragement of the guides, but I thought she was now a lost cause. Perhaps she may even have to be stretchered off the mountain. That being said, I certainly felt like turning back myself, and I’m sure everyone else was thinking Ashley was the only sane person in the group. For me though, failure was not an option. I had travelled half way around the world to do this and the weather up here was perfect – well as perfect as you can get at minus fifteen degrees in the small dark hours of the morning over five thousand metres above sea level. The rest of us (apparently of lesser sanity) continued ascending the mountain in the total darkness of night in single file following the boots of the person immediately in front of us leaving Ashley and Azaan behind. It was 2:20 AM. Half an hour had passed since leaving William’s Point. Out of the darkness I could see we were approaching another big rock at Sebastiaan Meyer Cave Point, now 5182 metres above sea level. I continued climbing and climbing, wondering when the rocks would begin. I noticed the track was going from side to side of the steep scree slope. It was now too steep for us to walk directly up the slope as we inched our way tiny step after tiny step in the insanely cold conditions. After what seemed like an eternity, it was still dark at four o’clock in the morning, but I could just see some large boulders up ahead in the inky black darkness clinging to the top of the scree slope, looking like they could dislodge themselves and roll down the precariously steep slope any time soon. These were the Jamaican Rocks. The altitude here was around five and a half thousand metres. There are stories as to why they are called this. It certainly wasn’t a Jamaican climate up here. A local legend says they were named because a Jamaican once reached this far up the mountain, looked up, and said “Bloody shit!” before turning around and walking back down. Another local legend says he slipped here falling to his death. In truth no one really knows what happened up here, but somehow the name has stuck.

Well so much for this being the easiest way up the mountain! I was very tempted to do the “bloody shit” thing and turn around myself. However I recalled Desmond saying the area around the boulders was the most difficult part of the climb. I had recalled other volcanoes I had climbed in the past. In every case the most difficult to climb parts had always been just before the rim of the crater. I was encouraged. If I could just get through this vertical maze of boulders to Gilman’s Point, then it will be relatively easy from there to the summit – hopefully. The route became a lot more erratic weaving between the boulders. I thought that very soon it will become like the pile of boulders at the summit of Mount Kinabalu necessitating scrambling, except I was now a good kilometre and a half higher, and wondered if I had the energy to be able to climb over them in such thin atmosphere. Fortunately the gravel underfoot seemed to stay with us as we negotiated our way around the boulders. Fortunately we had Jaseri who had obviously been up here so many times that he would know every boulder in this area intimately, and with that he would know the best path towards our unseen goal of Gilman’s Point. Suddenly we passed between two boulders and the slope levelled off. What a relief, a brief reprieve. There was a small clear area about two square metres in size surrounded by huge boulders. At the back of the clear area was a wooden sign that read; “You are now at Gilman’s Point 5681 M. AMSL. Tanzania. Welcome and Congratulations. It was 5:03 AM, five tortuous hours after leaving Kibo. The sky was still completely dark. We had reached the top of the crater making good time. From here there was another two hundred metres ascent to the summit over an hour and a half. Many climbers do not go any further than here - just two thirds of the climbers who make it to Gilman's Point successfully reach the summit. Would I be one of them? Gilman’s Point is named after Clement Gilman, an engineer and geographer working in Tanganyika from 1920 till his death in 1946. He climbed the mountain in 1921 and was the first to use the boiling point of water to determine its altitude. At this altitude water boils at eighty degrees Celsius. Amazingly I was not as exhausted or disillusioned as I had been going up the final part of Mount Kinabalu last year. Given the steepest part was behind us now and that I had done the last part surprisingly with relative ease. I decided so long as I don’t think of the downhill, the walk around the crater to the top should be relatively easy after the long climb. My energy was restored. Before pressing onwards I gave my camera to one of the guides Imara to take my picture. He took several with the flash, and most of them weren’t lined up. I didn’t realise it at the time, but this guide, who I would later find out was one of Jaseri’s sons, would be my guide to the summit, and back to Kibo. Thankfully a few of the photos turned out okay. Others in the group had a photo or two taken of them before those of us brave enough to venture to the top went on. Now I needed to make the decision - is this it, or do I go up to the summit. I felt in very good condition, so the choice was obvious. I will walk the final hour and a half to the summit. A few of us set off from Gilman’s Point around the crater towards the summit at 5:08AM after just a couple of minutes rest. At the time it was too dark and we were too rugged up in the minus fifteen degree temperature to tell who was who. I recognised Gary, Dawn and Vicky though, and had assumed Ashley would be back at Kibo by now. I guessed everyone who had made it up this far would press onto the summit. The conditions even up here were perfect with not a breath of wind. That surprised me. Most mountains I have climbed in the past had been windy at the top. I especially recalled one climb of Mount Ngauruhoe in New Zealand where it had been so windy at the summit I could hardly stand up, and when I did I was very worried about being blown into the deep crater. Other mountains though had been calm at the top, and thankfully this was one of them. It was bitterly cold as it was, so I was happy not to be contending with wind chill as well. The odds were looking good. It was still totally dark but I knew the sun will be rising soon. We needed our headlamps to see through the darkness which prevented a full appreciation of how bright the stars and moon would have been above us. It seemed we were walking in the inside of the crater, negotiating the well-worn track around precipitous bluffs in the almost total darkness. Aside from the crunching sound of my boots on the frozen gravel, and the sounds of other people’s boots as they shuffled onwards towards the summit, it was totally silent up there. There was not a breath of wind, and as expected, there were no animals. At this altitude the air would have been almost sterile. Without any plant or animal life up here there was nothing to pollute the air.

The sky started to lighten at about 5:50 AM, almost six hours out from our base camp at Kibo. The sky quickly brightened to a thin band of bright yellow with a thin orange line on the horizon. Further above that was a thin blue band which quickly morphed into the black sky. At lower altitudes, the sky would turn a grey colour, then eventually purple, but up here it was quite bright along the horizon, highlighting the craggy bluffs of the crater, where the little glow-worm like lights of the other travellers behind me were inching their way towards the summit. The bright sky would have been a good eight or nine hundred kilometres away, so it will still be some time before the brightness would reach this part of the sky. Further in the distance was Mawenzi Peak now a long way below us. The mighty mountain peak that had towered precipitously over us yesterday morning as we took the upper route from Horombo now seemed very small and far below us. I would never have thought about saying that about a massive jagged mountain peak standing over five kilometres high. The going was very slow now. Up here at about five thousand seven hundred metres above sea level, the air was only half the density of that at sea level. I struggled to breathe the vacuous air. It was incredibly thin and also bone dry.

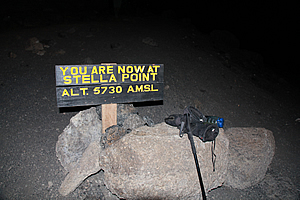

We stumbled over another bluff and dropped a few metres to where I saw a sign. It read “You are now at Stella Point, Alt 5730 AMSL”. This marked the end of a couple of the other routes up the mountain – the Machame route and Lemosho route. Here other climbers would reach the crater after their arduous climb up the mountain and continue onto the summit. It was now 6:15 AM. To the west it was still dark, but the eastern sky was significantly bright. I stopped here with my guide Imara to rest. Taking photos wearing gloves over mittens was virtually impossible, so I had to take off the climbing gloves to take the picture and put them down on one of the two rocks where the sign was wedged in between. Stella Point was named after a climber in the late 1800s who climbed the nearby rock which towered into a peak. He had summited this peak thinking it was the top of Kilimanjaro only to much later discover it wasn’t the highest peak. With the real summit in my sights now, nothing was going to stop me from reaching the top.

Looking back, the sky behind me was quite a lot brighter although it was still completely dark in front. For the first time though, I could see the rocks of the crater to the right starting to pick up some of the light of the rapidly brightening sky. Small patches of snow were highlighted over the purple brown rock. From here I could see more climbers ahead of me following the route now on the outside of the crater. The slope going away from the crater was a twenty to thirty degree slope and the slope into the crater was almost a sheer drop. Realising that my hands weren’t getting too cold, I pocketed my gloves.

I continued from Stella Point noticing the sky very quickly brightened over a matter of minutes. Down the outside of the crater I could see the glaciers I had seen from Horombo yesterday morning. Only they were a lot closer now. There were two of them. The nearer one to the left down the otherwise dead scree slope was the Rebmann Glacier, named after the explorer who first reported the ice cap covering the summit in 1848. A little beyond Rebmann Glacier was Decken Glacier. The two small Glaciers looked like something from the edge of the ice pack of Antarctica. The ice was a good ten to fifteen metres thick, but around the outside the walls were vertical. The ice at the base was around eleven thousand seven hundred years old. This would be where the sun would heat the rock below melting the retreating glacier.

During the 1800s the ice had covered the entire Kibo Peak. During the last ice age it had also covered the desert between Kibo and Mawenzi. The glaciers are rapidly retreating now with over eighty percent of the ice cover disappearing since 1912. It is believed the mountain will become completely ice free sometime between 2022 and 2033. I will be amongst the last of the climbers to see these glaciers. Looking down beyond the glaciers a layer of purple grey cloud surrounded the mountain at about four thousand one hundred metres. It was the same soft patchy mid-level cloud I had seen over Chile when flying between Iquique and Santiago. However this cloud only surrounded the mountain. More than about fifty kilometres away there was no cloud in any direction. This was dawning a fine sunny day.

Behind me Mawenzi Peak towered above the cloud, and the large plateau we had walked across yesterday afternoon was above the surrounding cloud. The cloud surrounding the mountain looked like huge foamy waves breaking on an island beach. Beyond that was a soft grey haze which covered the plains spreading out five vertical kilometres below. Although there was some distance to go to the summit, I already felt on top of the world. I was very close to the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro. The entire sky was a deep blue by now, so I turned off my head lamp. Ahead of me was a steep section of rubble leading to the summit. From here it was just one hundred and sixty five metres of climbing to go.

I inched my way up quite painfully, leaning on my pole as an old person would use a walking frame. It would have seemed ridiculous, but everyone else on the mountain was doing the same, struggling their way along very slowly. I began to feel disoriented as a headache began to form. I crossed my fingers hoping it wouldn’t get too severe. Just a hundred and fifty metres short of the summit and I was finally just beginning to experience symptoms of altitude sickness.

The symptoms were not severe though, so I continued towards the summit. It was just ahead of me now. Vicky was just a few metres ahead of me. Above the summit the moon stood very bright leading the way. To the right the barren crater loomed with the far side of the crater clearly visible on the other side, and more glaciers sitting on top of the distant ridge. A few metres behind me was Jaseri who was walking with Gary and Dawn.

Then at 6:27, six and a half hours after leaving Kibo, the sun suddenly rose over the distant horizon. It rose through the haze, then through a very thin band of mid-level cloud, highlighting some high cloud further beyond, perhaps fifteen hundred kilometres away over the Indian Ocean. Within seconds the sun was shining, highlighting on the tops of the glaciers, and illuminating their bright white and deep blue tones making them look like icebergs sitting on the barren volcanic regolith. This was especially so on the Furtwanger Glacier on top of a small plateau across the other side of the crater a good kilometre away.

I could now see clearly into the huge crater. Although it had not erupted for over three hundred and sixty thousand years, there were fumaroles active in the crater. Scientists believe there is molten rock just four hundred metres below the crater's surface. Activity has been measured just two hundred years ago, raising the status of the mountain to a dormant volcano. With magma so close to the surface who knows how soon it will be before it erupts again. A minute later at 6:33 the sun was already well above the distant clouds. Looking in the other direction as I walked I could clearly see the shadow of the mountain extending out some six hundred kilometres to the west, creating an amazing indigo shadow, even more impressive than the one I had seen from the top of Mount Kinabalu in Borneo last year.

From there I could see the summit, and the obvious wooden sign erected at the top. There were already about twenty climbers up there – it really was a bit of a crowd for such a hostile and barren place so far away from anywhere! I continued climbing, passing another glacier that was clean cut along the side. I could see layers in the face, indicating different climates over the years when the glacier. The white layers indicated times of plentiful snowfall, and the brown layers indicating periods of melt and dust storms.

Kilimanjaro was first attempted in 1861, but the climbers got no further than two thousand five hundred metres. One of the climbers had another attempt the following year reaching about four thousand three hundred metres, the level of the plateau between Kibo and Mawenzi. In 1887 Sebastiaan Meyer made his first attempt at the summit, but turned back at the base of Kibo not having the equipment to handle the steep snow and ice that covered the peak at the time. He made another attempt with two others the following year, but before they even reached the base of the mountain they were captured and held hostage until a ten thousand rupee ransom was paid.

In 1889 Meyer returned to Kilimanjaro with the Austrian Ludwig Pruscheller for a third attempt. They finally reached the summit on Purscheller’s fortieth birthday on 8 October 1889. From the summit they went down to climb Mawenzi Peak, spending a total of sixteen days above four thousand metres. It was 6:49 AM, twenty two minutes after sunrise, and nearly seven hours after leaving Kibo, that I reached the summit. The summit was plain Martian rock boulders exposed from the cover of glaciers. It had only been the last couple of decades that the top has been free of glacial ice.

A large wooden signpost stood there covered in little advertising stickers saying; “Congratulations, you are now at Uhuru Peak, Tanzania, 5895 M AMSL. Africa’s Highest Point, World’s highest free standing mountain”. I had done it. Uhuru is the Swahili name for freedom. There is a telling around mountaineering circles around the world that from here at the top of Kilimanjaro you can see more land than from anywhere else on the planet. Although there are higher mountains, none of them have such uninhibited views of the landscape around the summit. Here I was nearly as high as a jetliner – actually at the cruising altitude of a turboprop plane, but with uninhibited views without any portholes to look through. This truly was the place of freedom.

I gave my camera to Imara and he took several pictures of me as I briefly celebrated turning forty. There were a few small flags flapping around in what was now the gentlest of breeze. Behind me were a couple of people lying on the ground. I didn’t think that was a great idea though. There were even more people on the ground in front of me. Once my photo was taken, I moved away and sat down as I was suddenly feeling quite dizzy - the first signs of altitude sickness. Vicky and a couple of others got their photo taken as Dawn asked if I could get a photo of them. Their camera had died at Gilman’s Point. I was happy to oblige and fortunately managed to stand up to get a picture of them with Jaseri as he had been their guide up the last part of the mountain. I felt if I had remained sitting, I may have passed out into unconsciousness. Obviously climbing two thousand one hundred metres in one twenty four hour period – seven times the maximum my doctor recommended, was starting to take its toll. I was only at the summit for nine or ten minutes. The rising sun would have already increased the temperature to about minus 8 degrees, but we needed to head down.

For the first time in this trip, I started thinking of the downhill – From here there were nearly four vertical kilometres to drop to the start of the track at Marangu some forty eight kilometres away by tomorrow afternoon. Today, there is a drop of 2175 metres down to Horombo, something I just wasn’t looking forward to especially after such a long gruelling night climbing volcanic scree in sub-zero temperatures. I left the top with my guide Imara, and with Gary, Dawn and Jaseri. Thankfully it was easy going down the gravely summit towards Stella Point. By now it was light enough for the glaciers to stand out brilliantly in the sunlight.

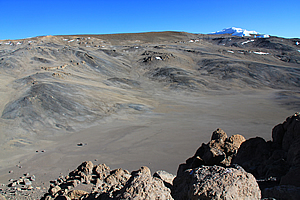

The moon was still high behind me, but it was as bright as the night moon would appear at sea level. Normally at low altitudes the moon fades a lot during daylight, but here the air was so thin that it retained its brightness. We reached Stella Point with reasonable ease before continuing along the route past all the bluffs over the crater. The view across the crater was amazing. It was completely barren apart from the odd patches of snow.

Looking ahead was another story though. Perhaps I should have put on my climbing goggles. The sun directly ahead of me now was extremely bright and shining straight into my face, so I couldn’t see ahead very well at all. I think some of the others got way ahead of me, but I still managed to negotiate the crater rim bluffs safely. It was 8:05 when I arrived at Gilman’s Point, just over an hour after leaving the summit. The downhill around the crater had been relatively easy, taking around half the time it had taken to go up. From here, I had my final view of the crater before heading down the Jamaican Boulders. The brownish grey crater was rather bare, but the crater walls on the other side had iceberg like glaciers. It was strange seeing these icebergs in the sky just five degrees from the equator, and over five kilometres up in the air. There was the Furtwangler Glacier (named after the leader of the fourth expedition to successfully reach the summit in 1912) standing dominant like heaped icing on top of a cake.

The crater itself was very Martian like, with the yellow grey rubble covering the surface. There were signs of liquid water that had rushed down the slopes into the bottom lunar crater. Here I put the camera away, and wouldn’t take any more pictures until leaving Kibo later in the day. Going down the Jamaican Boulders was fairly slow going, and I think this is where the others had all extended their lead from me. My guide Imara stayed with me though until we got to the top of the scree slope.

Like most scree slopes I had been on, the rubble was quite thin at the top. I could see all the way down the mountain where the track we had taken uphill had gone from side to side. Now I was taking the downhill along a slip going straight down. It was tough going to start with. I was using my pole, and Imara gave me one of his poles. Perhaps I should take two poles on these trips from now on. It was not long though before I reached the easier slope where the scree was thicker. Thankfully my gaiters kept all the stones out of my boots. I was making steady pace. My lips were also getting very dry. Finally we reached the cave at Sebastiaan Meyer Point where the slope gradually lessened. The huts at Kibo appeared to be a lot closer now. The scree became very thick, then suddenly quite thin again. I was on a roll, but still going slower than I should have been. Exhaustion was starting to set in now. I had been hiking for nearly eight hours now and knew there was still a long way to go to get down to Horombo. Finally we were near the bottom where the scree slope seemed to divide into several parts. By now I felt the air thickening, and could breathe easier. I kept looking at the hut, and it had the illusion of getting further away with increasing exhaustion. The cloud that had silently surrounded the mountain at sunrise was lifting now and enveloping us in patchy cloud as it rose up the slope. Now I was questioning my sanity. Why do I put myself through these tortuous treks? Sure going uphill and reaching mountain summits is great, but I can’t stand the downhills. This was the case in most mountains I have ever climbed in the past. Although the uphills were always gruelling and slower, it was the downhills that posed the most challenge for me. We walked in between two rock formations near the bottom of Kibo Peak before the hut suddenly reappeared. This time it was very close. What a relief. I was exhausted upon entering the hut at around 9:30, having walked for ten hours solid through tough conditions. It was deathly quiet in there and still freezing cold. Cloud had started overcoming the area, so there was no chance of it getting warmer than freezing today. I entered our bunkroom, and saw everyone else in my group, all fast asleep. They had all arrived here over the past half hour, and some less than ten minutes before me, but somehow they had all crashed. I was relieved that I was normal and not the only one completely exhausted from the ordeal. I was too exhausted and numb from the cold to even photograph the amazing view back up the mountain even though the cloud had temporarily cleared from the slope. I took off my water bottle and crawled back into bed. It was freezing in the room, but quickly the sleeping bag warmed and I fell asleep. I only got an hour of sleep before the Japanese group we were staying with returned. They had left shortly before my group last night, so their climb had taken about two hours more than ours. They were definitely a slower group, and a much noisier group waking us all up. They had all reached the Uhuru summit, even the one with the very bad cough. Although I was the slowest in our group going downhill from Gilman’s Point, it would therefore appear that I was in a very fast group. Before I could go back to sleep, Jaseri arrived and told us that lunch was ready. It was eleven o’clock in the morning. We all got up very stiff and very tired. I could hardly walk in the freezing cold. Looking at everyone else neither could they. Fortunately lunch was served in the very next room, where we were served soup and then some meat and vegetables. There we lethargically exchanged stories about our experiences up the mountain. We had all been in our own little worlds on the crater. Although I had seen Gary, Dawn, and Vicky at the top, I had assumed all the others apart from Ashley would have made it to the summit. It surprised me to learn that was not the case. I remembered Ashley had turned back just after William’s Point. I had assumed Azaan had taken her back to Kibo to recover. To my surprise not only did she end up reaching the summit, but she had arrived there shortly before I had. I didn’t even see her pass me. She recalled how she had felt incredibly sick over the lower half of the mountain and had convinced us she was pulling out, but amazingly the guide who had stayed with her had managed to convince her to continue all the way to the top. That’s what they are there for I suppose – helping make our dreams of insanity achievable.

Jono mentioned that as I was leaving Gilman’s Point with the others, he had experienced a very sudden and serious panic attack that somehow triggered very severe altitude sickness. He thought he was going to die. Mark and Azaan returned down the mountain with him. So much for the macho hero who insisted on taking his fifteen kilogramme pack all the way to Kibo, saying how crazy people were turning back at Gilman’s Point, and the insistence they would build a cairn at the top for their fellow Canadians they had met at Horombo. Honestly I thought that despite his cockiness he definitely was going to reach the summit even though I would have bet he would be the most likely person in our group to not make it. My initial thoughts had been correct. Azaan had managed to convince Ashley to continue the climb only to have to bring the Canadians down from Gilman’s Point. I’m sure he’s done the summit a lot of times before and having to take people down the mountain was just part of his job here. Mark showed us a photo of the sunrise they had taken from William’s Point cave at five thousand metres. It was a great shot, surprisingly similar to the one I had taken eight hundred metres higher when I was above Stella Point on my final approach to the summit. So it turns out that five of the seven of us in our group had reached the summit. I thought Mark had been incredibly noble in forgoing the summit to be with his son. Whatever the outcome, the worst of the challenge was over for all of us. From here it was a gently sloping walk back to the start of the track at Marangu forty two kilometres away. We packed up and left Kibo Hut at about one o’clock. The air was still freezing up here with a chill wind starting to blow. The hike up the road had been pretty epic yesterday, but it was a steady walk heading down. It was not steep, and gravity assisted us as we walked with a reasonable pace down the moderate grade road track, down towards the disgusting toilets at Jiwe La Ukoyo. Upon reaching the aluminium picnic tables, we briefly rested. We only stayed for a few minutes though as the sky was by now completely overcast as it had been yesterday when we crossed the plateau. With no sun, it was very cold so we decided to press on. From the junction we took the lower and shorter route towards Horombo. The track was very flat with a gradual downhill towards a gap between two barren hills. I thought the plateau could have perhaps been part of an old crater with most of the walls collapsed from perhaps a million years of erosion. Kibo was the most recent crater and Mawenzi Peak was the plug of what had been a much older volcanic cone. The plateau reminded me of Central Crater on the Tongariro Crossing in New Zealand. It was a flat area surrounded by active and dormant volcanic cones. This was very much the same, only much bigger. I also noticed the regolith here on the plateau was a lot redder than the top. It was very Mars like, whereas the top was grey and very lunar.

The cloud was now well above us, covering only Kibo and Mawenzi peaks. Conditions would be very rough at the top now. Soon I was seeing a few tufts of tussock to once more remind me that I was on Earth, and that we were entering a zone where things could live. There were huge boulders sitting randomly on the gravel. Most of us needed to use the toilet along that stretch, so we’d just find a rock to go behind. Only problem is that many thousands of other people over recent years have had the same idea, and there was a lot of waste and toilet paper around. The stench was pretty bad. Up here things in such cold conditions and the lack of living organisms things do take a long time to decompose.

It was about quarter past two when we went over the lip between the hills. The slope continued in a gentle downhill so technically it wasn’t a pass. Once across the lip the terrain changed a lot into the radial spurs and gullies draining any water from the hill now above us. The track responded by going up and down from spur to gully. Each downhill was a lot longer than the uphills though. There was a little more vegetation now, but it was still very barren up here. My legs were chafing again making the going a bit slower than I wanted it to. At least I could keep up with the rest of the group though. There were a lot of porters passing us now, carrying their heavy loads on their heads going from Kibo to Horombo as if it were just an easy walk in the park. They were carrying loads for more people who will be attempting the summit tonight. Thankfully that was behind me now.

About an hour later we reached a rest spot. A small sign indicated this was the last water hole before Kibo. Traditionally this was where people filled up their water bottles for the trip to the summit. For us this was the first source of water now that we were low enough. I still had plenty of water in my camelback, but my lips had cracked to the point they almost had no feeling in them. From here I could now see the long ridge rising from Horombo along which we had followed the other side just yesterday morning heading towards Mawenzi Hut junction on the upper route. It was hard to believe this was just yesterday morning. So much had happened since then.

The last hour or so to the hut was rather difficult going for me. I was starting to slow down and I gradually lagged behind the others who all seemed to be making good progress still. Jaseri stayed back with me. He seemed to be struggling too, but as our group leader, didn’t want to admit it. For him admitting he was struggling would cost him his job, and may cost the jobs of his sons as well. The others in our group very gradually extended a leg ahead of me upon leaving the last water hole. An hour passed and they were all about a hundred metres ahead of Jaseri and me. The air felt noticeably thicker now, but I was exhausted from having been walking for fourteen hours since midnight with only an hour of sleep and another hour of rest. It was very difficult going. Then I heard the soft thud of something falling. I looked back. Jaseri had fallen on the ground. I asked him if he is okay, and he stood up dusting himself. I stayed back with him to make sure he was okay, still keeping the pace I could handle. Soon afterwards he fell over again. I was getting a bit worried as he was 64 years old and perhaps getting frailer than he cared to accept.

It was about five o’clock when I finally reached Horombo. The cloud was quickly descending and quite foggy now. It was very quiet at the camp. Jaseri and I checked in, before he led me to my bunk room. My gear was in the room, and the others had arrived about five to ten minutes earlier and were already resting there. Thankfully my slightly slower pace wasn't too significant. I quickly unpacked, then went with the others to the far dining hut where we had dinner.

Dinner was rice with peas mixed in, a beef casserole, and plenty of hot tea. Despite such a massive day of achievement none of us had anything to say – we were all too exhausted to talk, even Mark who normally always had plenty of stories to tell. Perhaps he was quiet because he thought he was going to lose his son at Gilman’s Point early this morning. Once dinner was finished, we all slunk off to bed, exhausted from such a long day. We had another long day ahead of us tomorrow, but at least we would be spending tomorrow night back in the comfort of the Marangu Hotel, the best part of which will be a nice warm bath. I took off my anorak, crawled into the sleeping bag and fell asleep almost instantly along with the others. It had been a huge day. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||